When world growing darker around you, great men reached out to

ancient knowledge which became refuge to them, a private freedom to feel and

candle to see new world unfold. Very rarely, you read a book or article that

inspires you to see a familiar story in an entirely different way. Florence at

the dawn of the 15th century was extremely unusual, major trading center at the

heart of Tuscany and as a scaled down version of the 20th century globalized

world. She was in many respects one of the first of modern states. As

her painters and savants stood at the head of the Renaissance as the earliest

artists and thinkers of the modern world, so her politics were now emerging

from medievalism and taking a modern complexion.

With no king, prince or duke, the city was an independent

republic, run by the people, for the people. It was not a perfect democracy but

it worked and was responsible for creating a group of powerful families,

dynasties who vied with each other for political control of this thriving city.

The Florentine system did encourage an oligarchy of rival families to attain

positions of power, proving critical to the development of an enterprising,

peace-loving city, and fueling the competition which lay behind much of the

Renaissance. If I see our world with this renaissance era in mind and try to

contextualize the 20th century world from the Florentine historical point of

view I find many similarities between the our modern world and 15th century

Florence. As we have world certainly not unipolar but kind of oligarchy with

multipolar world in which powerful nations as those Florentine families

influencing the world, world is quite peace-loving too relative to our history,

fueling competitions of course as space race between USA and USSR is best

example of it and I do believe we are in the second renaissance phase as in

less than a single lifespan, we went from first manned flight to first man on

the moon. So 15th century Florence as a scaled down version of the

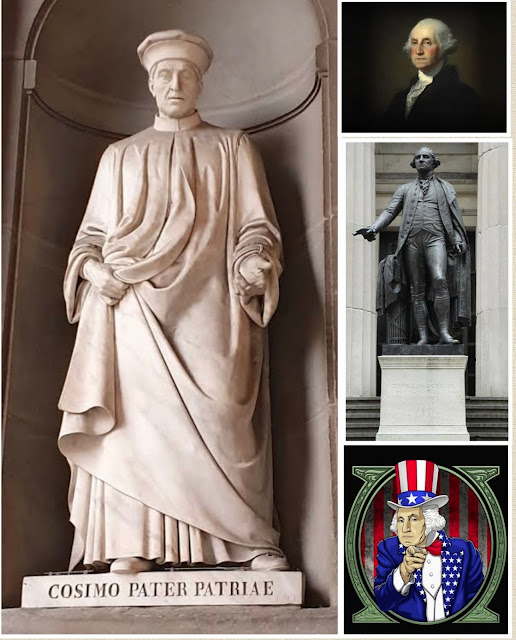

20th century globalized world. Medici family’s Rise and contribution in 15th

century Florence city and the same of USA in 20th century world has

some parallel implications.

Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici: USA before World War One

In Florence 1389 a boy was born into a medieval world, Cosimo de

Medici. He was not of noble birth but the son of a local wool merchant,

Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici who had risen from rural poverty through a

combination of aggressive salesmanship and financial caution. It was Giovanni's

founding of the family bank that truly initiated the Medici family's rise to

power in Florence.

Despite his growing wealth, Giovanni was diligent in his efforts

not to separate the Medici family from the other citizens in Florence. He did

so by continuously ensuring that he and his sons dressed and behaved like the

average working-class citizens of Florence. This was in part due to his desire

not to draw undue attention to himself and his family, and to ensure that,

unlike other wealthy families as one which the Albizzi of Florence, the Medici

remained in the favor of the population. The Albizzi were the de facto leaders

of an oligarchy of wealthy families that ruled Florence

and led the republican government, complex political system which was

‘democratic’ only on paper for two generations. By 1427, they were the most

powerful family in the city, and far richer than the Medici. They had been the

patrons of genius and cultural icons, but the family was more interested in

waging war than sustaining commercial viability. Rinaldo degli Albizzi was the

son of Maso degli Albizzi, a soldier and politician at the head of an ancient and

powerful their family. At the time when the Giovanni and his son

Cosimo were increasing their wealth and their popularity in Florentine

circles, the Albizzi became their fiercest opponents. It was clear

that the Medici were threatening their supremacy, stealing influence and

power. Giovanni’s hopes were to build a positive reputation of his family by

avoiding conflicts with the law and keeping the people of Florence happy. Giovanni

offered his son Cosimo a warning be wary of going to the palace of government

wait to be summoned, then show your selves obedient and never display any pride

always keep out of the public eye. His attitude is exemplified in his writings

to his son Cosimo, saying, "Strive to keep the people at peace, and the

strong places well cared for. Engage in no legal complications, for he who

impedes the law shall perish by the law. Do not draw public attention on

yourselves yet keep free from blemish as I leave you."

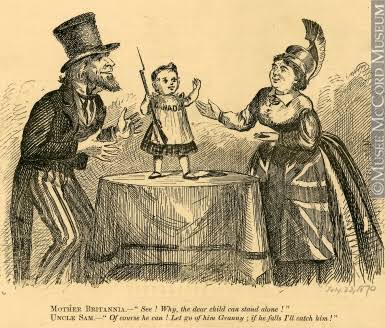

The same can be related to the USA’s attitude of the neutrality

as US President George Washington issued formal announcement, Proclamation of

Neutrality that declared the nation neutral in the conflict between France and

Great Britain. This was a longstanding idea at the heart of American foreign

policy that the USA would not entangle itself with alliances with other nations

which lasted even during world war one. In fact USA was not part of Vienna system,

the concert of powers when the great powers of the time which were France,

Russia, United Kingdom, Prussia (historically prominent German state), first

spark of international cooperation in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars to

coordinate their ambitions and activities avoiding future wars which broke later

down through the Crimean War. The US had historically steered clear of foreign

engagements, and the only war with a European power in generations had been the

Spanish-American war of 1898, which had not been widely supported popularly. The

industrial revolution produced explosive economic growth, and the bigger US

economy required a more centralized state and bureaucracy to manage the growing

economy. Power became concentrated in the federal government, making it easier

for expansionist presidents, like William McKinley, to unilaterally push United

States influence abroad dragged the country into war with Spain over the island

of Cuba despite intense opposition at home.

Giovanni stayed at arm’s length from politics for much of his life, but he was urged to reluctantly accept various positions of high office throughout his life in the Signoria of Florence because of the prestige and universal popularity he enjoyed in the city. World War I showed how much America’s influence had grown. Not only was American intervention a decisive factor in the war's end. But President Wilson attended the Paris Peace Conference which ended the war and attempted to set the terms of the peace. He spearheaded America’s most ambitious foreign policy initiative yet, an international organization, called the League of Nations, designed to promote peace and cooperation globally. The League, a wholesale effort to remake global politics, showed just how ambitious American foreign policy had become. Yet isolationism was still a major force in the United States. Congress blocked the United States from joining the League of Nations, dooming Wilson’s project, like the same way as Giovanni’s reluctance towards getting involved in Florentine politics.

Original Sin: Astute Decision: Rise to Power

Wilson’s Republican

opponents men like Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Cabot Lodge, and Elihu Root wished

to see America take its place among the powers of the earth. They wanted a

navy, an army, a central bank, and all the other instrumentalities of power

possessed by Britain, France, and Germany. These political rivals are commonly

derided as “isolationists” because they mistrusted the Wilson’s League of

Nations project. That’s a big mistake. They doubted the League because they

feared it would encroach on American sovereignty. It was Wilson who

wished to remain aloof from the Entente, who feared that too close an

association with Britain and France would limit American options. This

aloofness enraged Theodore Roosevelt, who complained that the Wilson-led United

States was “sitting idle, uttering cheap platitudes, and picking up [European]

trade, whilst they had poured out their blood like water in support of ideals

in which, with all their hearts and souls, they believe.” Wilson was guided by

a different vision: Rather than join the struggle of imperial rivalries, the

United States could use its emerging power to suppress those rivalries

altogether. Wilson was the first American statesman to perceive that the United

States had grown into a power unlike any other. USA had emerged, quite

suddenly, as a novel kind of ‘super-state,’ exercising a veto over the

financial and security concerns of the other major states of the world.

Giovanni befriended

the Neapolitan cardinal Baldassare Cossa, a former pirate who had embarked on

an alternative career in the church and had ambitions to enter the Vatican even

to become Pope himself, all he needed was a campaign fund. During the Western

Schism of 1378, also called Papal Schism which was a split within

the Catholic Church lasting from 1378 to 1417 in which two men

simultaneously claimed to be the true pope, and

each excommunicated the other. It was resulted during the returning

of papacy back to Rome again from Avignon which was there for 67 years. The

pair of elections threw the Church into turmoil. There had been

rival antipope claimants to the papacy before, but most of them had

been appointed by various rival factions; in this case, a single group of

leaders of the Church had created both the pope and the antipope. In May 1408

Baldassare was one of the seven cardinals who deserted Pope

Gregory XII, and convened the Council of Pisa. Cossa became the

leader of a group whose objective was to finally end the schism. The

result was silly beyond belief as they deposed Pope Gregory XII and Anti-Pope

Benedict XIII and elected a third Pope Alexander V in 1409. As

the two existing popes Gregory and Benedict who clearly enjoying their current

positions of power simply ignored this decision and there were now not just two

Popes but three. So at the beginning of the 15th century the papal

curia was divided amongst three centers, Avignon, Pisa and Rome, with popes in

each city. Anti-Pope Alexander V was not long for this world and died soon

after his promotion leaving the way clear for Baldassare himself, only

made an ordained priest on 24th May 1410, to

be consecrated as Pope John XXIII on 25 May 1410.

Giovanni knew that the

church was in chaos, papacy itself was up for grabs and with enough money even

Cossa stood a chance of success Giovanni dared to back the unlikely outsider.

As a supporter of Baldassare Cossa, Giovanni had loaned his money in an astute

way at an important point, it was an enormous gamble for their local business.

Baldassare Cossa was elected Pope John XXIII and the first thing he made

the Medici Bank the bank of the papacy, contributing considerably to

the family's wealth and prestige. This reward from his friend in 1413 was for

the Medici Bank to get the Curia, a near monopoly of the bank account of

the Papal Estates. All the tithes and taxes that flow to the Curia from London

to Tunisia would pass through Medici Bank. In a stroke, Medici bank became the

most successful bankers in Europe. The Rome branch of the Medici

bank became easily the most profitable (+50% of their revenues). Although

Pope John XXIII was himself deposed in 1415 on this 2-year papal gift was built

the financial infrastructure that made the Medici family the most powerful

family in Florence city.

Neither Giovanni

caused Western Schism nor did USA start World War one but with their astute

decision that helped pave the way for Power in the 15th century

Florence City for Medici and in the 20th century world for USA.

War and The Collapse of the old order

Florence in the 15th century

was a city unlike anywhere else new this major trading center the heart of

Tuscany and the manufacture of textiles became a major industry. Before Medici

arrival in banking, the most prominent of financial houses to extend their

operations beyond the Alps were The Florentine houses of the Acciaiuoli (with

53 branches throughout Europe), the Peruzzi (83 branches), and the Bardi (even

larger than the Peruzzi). These firms traded in agricultural commodities and

industrial products, especially woolen textiles, for which Florence was a major

center of production, but they drew much of their profit from fees levied on

exchange of currency. These fees also served as a legal screen behind which

they concealed the practice of usury (charging interest on loans), a practice

outlawed by canon law. Conducting large-scale commercial and credit business

over great distances was risky. The Florentine banks flourished because they

had better and more current economic information than those they did business

with.

In the 14th century,

Italian states raised these troops in ever larger numbers not by hiring

individuals but by drawing up a condotta (contract) with a condottiere

(contractor), who would engage to bring a band of up to several thousand

soldiers in time of war to the aid of a commune or kingdom. Given the

difficulties of securing political control over Italian military leaders (who

might, it was feared, take over the state), it became common, beginning in the

1330s, to negotiate with non-Italian condottieri. Their forces rapidly grew to

immense size. In the 1350s “The Great Company,” founded by Werner of Urslingen,

comprised some 10,000 troops and 20,000 camp followers and had its own

government, consultative council, bureaucracy, and foreign policy. Throughout

the 1360s these “mobile states”, for example, the companies of the Englishman

Sir John Hawkwood and the Germans Albrecht Sterz and Hannekin Baumgarten dominated

war in Italy, and in times of peace they were all too likely to subject their

former employers to a variety of blackmailing threats.

These changes in the

practice of war went hand in hand with a considerable expansion in the power of

governments. The weak, decentralized communes of the 13th century,

with comparatively primitive administration and very light taxation, gave way

in the 14th century to republics and signorie

with much stronger political control and exclusive new means of fiscal

exploitation. States raised revenues through property taxes, gabelle (e.g.,

taxes on contracts, sales, transport of goods into and out of town), and forced

loans (prestanze), while they developed sophisticated measures, including the

consolidation of state debts into a form of national debt, to service long-term

deficit financing. At Florence, for example, where from 1345 state debtors were

issued securities at 5 percent interest, negotiable in the open market,

revenues rose from around 130,000 florins in the 1320s to more than 400,000

florins in the 1360s. These innovations allowed war to be waged on a larger

scale, and states increasingly diverted productive wealth into war. That is,

these innovations helped cause the setbacks that occurred in many sectors of

the economy during the 1340s. In that decade, with trade already disrupted by

the beginning of the Hundred Years’ War

in France, the overextension of Florentine banks became clear. In 1343 the Peruzzi

company collapsed, in 1345 the Acciaiuoli, and in 1346 the Bardi.

Extension of credit was the most risky activity of all, and Florentine

banks discovered this to their sorrow. They

made the mistake of lending vast sums to King Edward III of England during the

1330s as he prepared for the conflict with France that became the Hundred

Years’ War. The bankers soon realized that they had extended too much

credit, but since they had already lent so much, they felt compelled to lend

more, lest they lose what they had already lent. By 1343, when it became

obvious that King Edward III was not going to score a speedy victory, the king

repudiated his debts to the unpopular foreign bankers. He borrowed 600,000 gold

florins from the Peruzzi banking family and another 900,000 from the Bardi

family. While the banks perished, Florentine literature flourished, and

Florence was home to some of the greatest writers in Italian history: Dante,

Petrarch and Boccaccio. Banks come and go, after 500 years people remembers Medici

than other bankers for their patronage to art, science and philosophy which

still influences us today. Some economic historians have concluded that this

collapse of the early Florentine banks was a major cause of a great depression that

lasted beyond the 1340s. The trouble was their commitment to King Edward III

had grown so much to borrow a phrase from 20th century world “too

big to fail”.

Centuries of

prosperity ruined by a single unpaid loan to the King of England. The Medici

banned loans to princes and kings, who were notoriously bad investments. The

Medici also kept ahead of their banking rivals because of the invention of limited

liability and set up a franchise system, where regional branch managers shared

a stake in the business. Consequentially, the Medici business remained in the

black while its competitors lost fortunes. On the other hand, for The Albizzi

regime war was the instrument of their power and they prosecuted them endlessly.

They contributed to Florence’s expansion over Tuscany, which since the

mid-14th century had transformed the city-state into a territorial state like

Milan and Venice. The city had absorbed Volterra in 1361 and Arezzo in

1384; then it went on to conquer Pisa, with its port, in 1406 and to

purchase Livorno from Genoa in 1421. Beginning

in 1389, Gian Galeazzo Visconti of Milan expanded his dominion into the Veneto,

Piedmont, Emilia and Tuscany. During this period Florence, under the leadership

of Maso degli

Albizzi was involved in three wars with Milan (1390–92, 1397–98,

and 1400–02). The Florentine army, commanded by John Hawkwood, contained the

Milanese during the first war. The second war started in March 1397. Milanese troops

devastated the Florentine contado, but were checked in August of that year. The

war expenses exceeded one million florins and necessitated tax raises and

forced loans. A peace agreement in May 1398 was brokered by Venice, but left

the struggle unresolved. Over the next two years Florentine control of Tuscany

and Umbria collapsed. Pisa and Siena as well as a number of smaller cities

submitted to Gian Galeazzo, while Lucca withdrew from the anti-Visconti league,

with Bologna remaining the only major ally.

Gabriele Maria Visconti sold Pisa to the Republic of Florence

for 200,000 florins. Since the Pisans did not intend to voluntarily submit to

their long-time rivals, the army under Maso degli Albizzi took Pisa on 9 October

1406 after a long siege, which was accompanied by numerous atrocities. The

state authorities had been approached by the Duchy of Milan in 1422, with a

treaty, that prohibited Florence's interference with Milan's impending war with

the Republic of Genoa. Florence obliged, but Milan disregarded its own treaty

and occupied a Florentine border town. The conservative government wanted war, while

the people bemoaned such a stance as they would be subject to enormous tax

increases. The republic went to war with Milan, and won, upon the Republic of

Venice's entry on their side. The war was concluded in 1427, and the Visconti

of Milan was forced to sign an unfavorable treaty.

The debt incurred during the war was gargantuan, approximately 4,200,000

florins. To pay, the state had to change the tax system. The current estimo system

was replaced with the catasto. In the sphere of politics, Giovanni di Bicci de’

Medici stayed true to his reputation and the tradition of the Medici family as

champions of the people and intractable opponents of the nobility of Florence.

In 1426, he exerted his considerable personal influence in the Signoria to

replace Florence's inequitable and oppressive poll tax with

the Catasto. This was a more regular property tax devised by Giovanni, which

lifted the tax burden from the poorer classes in Florence and made it more

difficult for the nobility to evade their share. The catasto was based

on a citizen's entire wealth, while the estimo was simply a form of

income tax.

Rinaldo degli Albizzi was

a soldier and a diplomat from an early age. His main goals were to

keep the oligarchy in power and defeat Florence’s enemies at all costs. When

his father died in 1417, Rinaldo took his place at the head of the Albizzi

family and started a war to conquer Lucca Seeking further expansion.

But this enterprise turned out to be more difficult than he thought, and cost

Florence dearly. He failed to conquer Lucca in a war fought between

1429 and 1433. By 1430, Albizzi’s military policy had cost the Florentine

taxpayer a fortune and much of their support. War of Lucca and its failure was

largely responsible for the fall of the oligarchy dominated by the Albizzi and its

replacement with an oligarchy subordinate to Cosimo de’ Medici. During this campaign, Rinaldo, while serving

as War Commissioner under the Ten of war, was accused of attempting to

increase his own wealth through sacking. He was eventually removed from his

position and recalled to Florence. Pragmatic pacifists marshaled around Cosimo

de’ Medici.

The German delegates just

like Albizzi were presented with a fait accompli during the treaty of Versailles which

was drafted during the Paris Peace Conference in the

spring of 1919 in a politically charged atmosphere after World War I. The five

leading victors created a Council of Ten the heads of government and their foreign

ministers. The population and territory of Germany was reduced by about 10

percent by the treaty. The war guilt clause of the treaty deemed Germany the

aggressor in the war and consequently made Germany responsible for making reparations

to the Allied nations in payment for the losses and damage they had sustained

in the war. To make sure that Germany would never again pose

a military threat to the rest of Europe, and the treaty contained a

number of stipulations to guarantee this aim. The German army was restricted to

100,000 men; the manufacture of armored cars, tanks, submarines, airplanes, and

poison gas was forbidden. All of Germany west of the Rhine and up to

30 miles (50 km) east of it was to be a demilitarized zone. The forced

disarmament of Germany, it was hoped, would be accompanied by voluntary

disarmament in other nations. The treaty included the Covenant of

the League of Nations, in which members guaranteed each other’s

independence and territorial integrity. Economic sanctions would be applied against

any member who resorted to war.

The four years’

carnage of World War I was the most intense physical, economic, and

psychological assault on European society in its history. The damage wrought by

war would live on through the erosion of faith in 19th-century liberalism,

international law. Whatever the isolated acts of charity and chivalry by

soldiers struggling in the trenches to remain human, governments and armies had

thrown away. World War I subordinated the civilian to the military and the

human to the machine. France, which suffered more in material terms than any

World War I belligerent except Belgium. Northeastern France, the country’s most

industrialized region in 1914, had been ravaged by war and German occupation.

Millions of men in their prime were dead or crippled. On top of everything, the

country was deeply in debt, owing billions to the United States and billions

more to Britain. France had been a lender during the conflict too, but most of

its credits had been extended to Russia, which repudiated all its foreign debts

after the Revolution of 1917 (Yes, Same story like Bardi bank with King of

England in 1340 as Lenin regime repudiated the tsarist debts to Britain and

France). The French solution was to exact reparations from Germany. Britain was

willing to relax its demands on France. But it owed the United States even more

than France did. Unless it collected from France, Italy and all the other

smaller combatants as well, it could not hope to pay its American debts. The

foundation stone of prewar financial life, the gold standard, was shattered,

and prewar trade patterns were hopelessly disrupted. The war weakened the

European powers vis-à-vis the United States and Japan, destroyed the prewar monetary

stability, and disrupted trade and manufactures. World War I also overthrew the

power structure in East Asia and the Pacific. Before 1914 six imperial rivals

had struggled for concessions on the East Asian coast. But the war eliminated

Germany and Russia from colonial competition and weakened Britain and France,

leaving the United States, Japan, and China in an uncomfortable triangular

relationship that would persist until 1941. And the empires like Hohenzollern,

Habsburg, Romanov, and Ottoman had fallen. The old was bankrupt. It remained

only to decide which newness would take its place.

World War I was a significant turning point in the political, cultural, economic, and social climate of the world. The war and its immediate aftermath sparked numerous revolutions and uprisings. The Big Four (Britain, France, the United States, and Italy) imposed their terms on the defeated powers in a series of treaties agreed at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, the most well-known being the German peace treaty: the Treaty of Versailles. Ultimately, as a result of the war, the Austro-Hungarian, German, Ottoman, and Russian Empires ceased to exist, and numerous new states were created from their remains. However, despite the conclusive Allied victory (and the creation of the League of Nations during the Peace Conference, intended to prevent future wars), a second world war followed just over twenty years later.

Salvestro de’ Medici and

Ciompi Revolt: USA before independence and Age of Revolution

The conflict of religious and political ideology emerged chiefly

in the second half of the 13th century, but later debates often hearkened to

the vituperative papal-imperial propaganda of the 1240s. The emergence of

papalist and imperial parties that later in the century called themselves Guelf

and Ghibelline, respectively. The Ghibellines were supporters of the noble

rulers of Florence, whereas the Guelphs were populists. In 1304, the war

between the Ghibellines and the Guelphs led to a great fire which destroyed

much of the city. The communes of the 13th century had become increasingly dominated

by the conflicts of the nobility who controlled their governments. These

divisions, though often moved by the Guelf and Ghibelline parties, in fact

largely reflected personal, economic, or quite local political rivalries—all

inflamed by ideals of chivalric honor and an everyday acceptance of the

traditions of vendetta. In large part as a response to these conflicts, there

had arisen within the communes the movement of the popolo i.e., of associations

of non-nobles attempting to win a variety of concessions from the nobility. Within

the ranks of the popolo were, in the first place, those who had gained wealth

through trade, banking, exercise of a profession, or landholding and sought membership

in the ruling noble oligarchies. The second group comprised prosperous members

of the artisan or shopkeeping classes who, while not normally seeking a direct

position in government, sought a more satisfactory administration of the

finances of the commune (particularly a more equitable distribution of taxation),

a greater voice in matters that most directly concerned them (for example, the

licensing of the export of food), and, in particular, the impartial administration

of justice between noble and non-noble. Above all, the popolo (like many of the

nobility themselves) desired a civic order that would end violent party

conflicts and lessen the effects of noble vendettas. In some towns the popolo

movement succeeded in bringing about constitutional change. In those communes

where the nobility did not monopolize all wealth and where the development of

trade, industry, and finance had created a complex social structure, the

existing oligarchies agreed to come to terms. This came about more easily when

the popolo succeeded in ending party struggles so violent that they could be

described as a form of civil war. Up to the beginning of the 1340s, Florence

reigned supreme in long-distance trade and in international banking. From that

time, grave shocks struck its economy, and these, combined with failure in war,

led to another brief experiment in signorial rule; as Florence requested for

support in protecting Guelph interests in 1342 a protégé of King Robert of

Naples, Walter of Brienne, titular duke of Athens, was appointed signore for one

year. Almost immediately on his accession, Walter changed this grant to that of

a life dictatorship with absolute powers. But his attempt to ally himself with

the men of the lower guilds and disenfranchised proletariat, combined with the

introduction of a luxuriant cult of personality, soon brought disillusion. An

uprising in the following year restored, though in a rather more broadly based

form than hitherto, the rule of the popolo grasso (“fat people”). Florentine ruling class of wealthy merchants

called upon him to rule the city. Since 1339, Florence had been in the grip of

a severe economic crisis brought about by immense English debts to Florentine

banking houses, and by astronomical public debts incurred in trying to obtain the

nearby city of Lucca. The Florentine nobility looked to foreign powers to solve

the city's seemingly impossible financial problems, and found an ally in Walter

of Brienne. Although the ruling class invited Walter to rule for a limited

time, the lower classes, who were fed up with the ineptitude of Walter's

predecessors, unexpectedly proclaimed him signore for life. Walter VI ruled

despotically, ignoring or directly opposing the interests of the very same

merchant class that had brought him to power. The "Duke of Athens"

imposed harsh economic correctives on the Florentines, including the flat tax

estimo, and prestanze, postponements of the city's repayment of loans forced

from the wealthier citizens. These measures both angered the Florentines, and

helped alleviate the fiscal crisis that had been stewing for years. After only

ten months, Walter of Brienne's Signoria was cut short by conspiracy. Walter VI

was not only forced to resign from office, but barely escaped Florence with his

life.

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution

which occurred in colonial North America between 1765 and 1783. The American in

the Thirteen Colonies defeated the British in the American Revolutionary War

(1775–1783), gaining independence from the British Crown and establishing the

United States of America, the first modern constitutional liberal democracy.

The opening shots of the American Revolution on Lexington Green in the Battle

of Lexington and Concord is referred to as the “shot heard ‘round the world”,

which were fired on 19th April 1775. The American Revolution not

only established the United States, but also ended an age of monarchy and began

a new age, an age of freedom. It inspired revolutions around the world. The

United States has the world’s oldest written constitution, and the constitutions

of other free countries often bear a striking resemblance to the US

Constitution – often word -for-word in places. After the Revolution, genuinely

democratic politics became possible in the former American colonies. The rights

of the people were incorporated into state constitutions. Concepts of liberty,

individual rights, equality among men and hostility toward corruption became

incorporated as core values of liberal republicanism. The greatest challenge to

the old order in Europe was the challenge to inherited political power and the

democratic idea that government rests on the consent of the governed. The

example of the first successful revolution against a European empire, and the

first successful establishment of a republican form of democratically elected

government, provided a model for many other colonial peoples who realized that

they too could break away and become self-governing nations with directly

elected representative government. The American Revolution was the first wave

of the Atlantic Revolutions: the French Revolution, the Haitian Revolution, and

the Latin American wars of independence. Aftershocks reached Ireland in the

Irish Rebellion of 1798, in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and in the

Netherlands. A revolutionary wave followed, resulting in the creation of a

number of independent countries in Latin America. The Haitian Revolution lasted

from 1791 to 1804 and resulted in the independence of the French slave colony.

The Peninsular War with France, which resulted from the Napoleonic occupation

of Spain, caused Spanish Creoles in Spanish America to question their

allegiance to Spain, stoking independence movements that culminated in various

Spanish American wars of independence (1808–33), which were primarily fought

between opposing groups of colonists and only secondarily against Spanish

forces. At the same time, the Portuguese monarchy relocated to Brazil during Portugal's

French occupation. After the royal court returned to Lisbon, the prince regent,

Pedro, remained in Brazil and in 1822 successfully declared himself emperor of

a newly independent Brazil. From 1807 to 1830, you have a series of revolutions in Latin

America, many of which were led by Simon Bolivar, who was a Creole, Venezuelan.

Once Spain and Portugal are fighting Napoleon coupled with the ideas of the

Enlightenment and the examples of the United States and Haiti, it inspires a

whole other series of revolts in Latin America, many of which were led by Simon

Bolivar. And so by the time we get to 1850, much of the European imperialism in

the Americas has come to an end. Spain

would lose all three of its remaining Caribbean colonies by the end of the

1800s. The most severe blow to Great Britain’s 18th-century dreams of empire,

however, came from the revolt of the 13 American colonies. These contiguous

colonies were at the heart of the old, or what is often referred to as the

first, British Empire, which consisted primarily of Ireland, the North American

colonies, and the plantation colonies of the West Indies. The shock of defeat

in North America was not the only problem confronting British society.

Ireland—in effect, a colonial dependency—also experienced a revolutionary

upsurge, giving added significance to attacks by leading British free traders

against existing colonial policies and even at times against colonialism itself.

But such criticism had little effect except as it may have hastened colonial

administrative reforms to counteract real and potential independence movements

independencies such as Canada and Ireland. The aftermath of American independence

was a diversion of British imperial interests to other areas such as Australia

and India. The Marāthās, the main

source of resistance to foreign intrusion, were decisively defeated in 1803,

but military resistance of one sort or another continued until the middle of

the 19thcentury. The financing and even the military manpower for this

prolonged undertaking came mainly from India itself.

At the Congress of

Vienna, Prince Metternich and his allies tried to extinguish the fires of

social ferment and prevent another French Revolution. But despite the Congress

of Vienna’s determined efforts to prevent them, reform and activism heated up

after 1815 alongside industrialization. In the 19th century, people were

looking inward at the domestic policies of each kingdom or state, which was a

sharp difference from the early modern period when kingdoms were constantly fighting

one another with domestic issues being much less of a concern. But much of what

was happening outside of Europe did affect Europe, of course. In the 1810s and

1820s, for instance, North, Central, and South American people gained their

independence from Portugal and Spain. By 1830, colonists’ victories put

mainland Spain at its weakest in three centuries. So, while distant ferment

liberated much of the Spanish and Portuguese empires, within post-Napoleonic

Europe, citizens’ groups of all sorts blossomed across the continent and

reformist uprisings against rulers flourished. In Naples the victorious powers

made sure that the Bourbons would not repeat the reprisals of 1799. Thus, the

restoration appeared to begin well under the balanced policies of a government

led by Luigi de’ Medici, who absorbed part of Murat’s capable bureaucracy. Many

judicial and administrative reforms of the French era survived, but concessions

made to the church in a concordat concluded in 1818, as well as financial

retrenchment, hampered the progress of the bourgeoisie. Especially among the galantuomini, who had profited from

French legislation, strong discontent found an outlet in a widespread secret

society, I Carbonari (“The Charcoal

Burners”). So in Italy, the Carbonari,

a secret society aiming for constitutional government in parts of Italy,

directed uprisings in 1820 and 1830. But the forces of the Holy Alliance of

Austria, Prussia and Russia put down both revolts. Also during these decades,

Hungarian nobility, also operating in Metternich’s orbit, lobbied for

separation from the Austrian empire, but without much luck. Serbia and Greece

had more success in pulling away from the Ottomans. The Serbs became an

independent principality under the Ottomans in 1817 after an uprising in 1815.

And the Greeks won complete independence from the Ottomans in 1831. On 27th,

28th and 29th July 1830, Known as the “Three Glorious

Days” of July 1830, the rioters erected barricades in the streets and

confronted the army in bloody combat, resulting in more than one thousand dead,

Charles X and the royal fled from Paris. They installed Charles’s cousin

Louis-Philippe as king and created a constitutional monarchy. The new king

Louis-Philippe expanded voting rights, known as suffrage, to around 170,000 men,

but that was still a tiny fraction of the 30 million French citizens. Social

unrest remained high as France became a more industrialized economy with more

people living in cities. Both living and working conditions for common people

were often terrible. After adopting reforms in

the 1830s and the early 1840s, Louis-Philippe of France rejected further change

and thereby spurred new liberal agitation. Artisan concerns also had quickened,

against their loss of status and shifts in work conditions following from rapid

economic change; a major recession in 1846–47 added to popular unrest. Some

socialist ideas spread among artisan leaders, who urged a regime in which

workers could control their own small firms and labor in harmony and equality.

A major propaganda campaign for wider suffrage and political reform brought

police action in February 1848, which in turn prompted a classic street rising

that chased the monarchy (never to return) and briefly established a republican

regime based on universal manhood suffrage.

In June 1840 the British fleet arrived at the mouth of the Canton

River to begin the Opium War. The Chinese capitulated in 1842 after the fleet

reached the Yangtze, Shanghai fell, and Nanking was under British guns. The

resulting Treaty of Nanking which stated that Britain got Hong Kong and five other treaty

ports, as well as the equivalent of two billion dollars in cash. Also, the Chinese

basically gave up all sovereignty to European spheres of influence, wherein Europeans

were subject to their laws, not Chinese laws. Other

countries soon took advantage of this forcible opening of China; in a few years

similar treaties were signed by China with the United States, France, and

Russia. The Chinese, however, tried to retain some independence by preventing

foreigners from entering the interior of China. With the country’s economic and

social institutions still intact, markets for Western goods, such as cotton

textiles and machinery, remained disappointing: the self-sufficient communities

of China were not disrupted as those in India had been under direct British

rule, and opium smuggling by British merchants continued as a major component

of China’s foreign trade. Western merchants sought further concessions to

improve markets. But meanwhile China’s weakness, along with the stresses

induced by foreign intervention, was further intensified by an upsurge of

peasant rebellions, especially the massive 14-year Taiping Rebellion (1850–64).

By the end of 1848,

France, the Austrian Empire, Denmark, Hungary, the Italian States, and even

Poland would be enmeshed in the greatest wave of revolutions Europe has ever

seen. Many Europeans were experiencing the “Hungry Forties,” caused once again

by bad harvests and especially in Ireland the potato blight, a mold that

devastated potato crops in Ireland and elsewhere in Europe. The problem was

made worse by several aspects of what might be called economic modernity—that

is, standardization, one-crop agriculture, and more efficient wholesaling of

food. In terms of standardization and one-crop agriculture, traditionally Peru

had at least 4-5,000 types of potatoes. So if one type contracted a specific

blight, there were still several thousand other varieties that might be safe.

But Europe, followed by the United States, was gradually turning toward farms

that focused on a single crop, and often a single strain of a crop, for

efficiency. Increasingly, imperialists forced this standardization and single

crop farming on other parts of the world, raising the chances for disaster.

Because of the single strain of potato, blight devastated entire crops. And

this resulted in death from starvation and diseases that invaded the weakened

bodies of at least a million Irish farmers and their families. Another million

or more emigrated, some to England and others to the United States and Canada

(where in both cases, by the way, there were no laws creating a distinction

between legal and illegal immigration. People simply moved in.). And as

scarcity deepened in 1846 and 1847, Britain’s liberal Whig government stuck to

its belief in laissez-faire, meaning that the government should let events play

themselves out, and therefore offered the Irish no help at all. The system of

usually English landlords requiring payment from Irish peasants to work

farmland also worsened the crisis--like, throughout the Irish famine, huge

amounts of food were exported from Ireland to England. Also, amid all this

deprivation and death, anti-slavery and pro-freedom ideas were circulating. Britain

in between 1833-1838 freed slaves across the empire, except in India. A system

of slave-like indentured labor did spring up, but the rhetoric in Europe at

least, was one of emancipation. In Eastern Europe, Moldavia and Wallachia began

freeing several hundred thousand enslaved Roma in 1843. Later, in 1848, France

also re-emancipated slaves after their re-enslavement under Napoleon. These

events were accompanied by popular abolitionism, and uprisings, and the

development of a language of freedom, especially freedom from governmental and

structural oppression. Revolt quickly spread to

Austria, Prussia, Hungary, Bohemia, and various parts of Italy. These risings

included most of the ingredients present in France, but also serious peasant

grievances against manorial obligations and a strong nationalist current that

sought national unification in Italy and Germany and Hungarian independence or

Slavic autonomy in the Habsburg lands. New regimes were set up in many areas,

while a national assembly convened in Frankfurt to discuss German unity. The

major rebellions were put down in 1849. Austrian revolutionaries were divided

over nationalist issues, with German liberals opposed to minority nationalisms;

this helped the Habsburg regime maintain control of its army and move against

rebels in Bohemia, Italy, and Hungary (in the last case, aided by Russian

troops). Parisian revolutionaries divided between those who sought only

political change and artisans who wanted job protection and other gains from

the state. In a bloody clash in June 1848, the artisans were put down and the

republican regime moved steadily toward the right, ultimately electing a nephew

of Napoleon I as president; he, in turn (true to family form), soon established

a new empire, claiming the title Napoleon III. The Prussian monarch turned down

a chance to head a liberal united Germany and instead used his army to chase

the revolutionary governments, aided by divisions between liberals and

working-class radicals. Despite the defeat of the revolutions, however,

important changes resulted from the 1848 rising. Manorialism was permanently

abolished throughout Germany and the Habsburg lands, giving peasants new

rights. Democracy ruled in France, even under the new empire and despite

considerable manipulation; universal manhood suffrage had been permanently

installed. Prussia, again in conservative hands, nevertheless established a

parliament, based on a limited vote, as a gesture to liberal opinion. The

Habsburg monarchy installed a rationalized bureaucratic structure to replace

localized landlord rule.

The American Revolution not only got rid of a king, it

profoundly changed society itself. Prior to the Revolution, everyone except the

king had their "betters." Society was layered, with the king at the

top, then the peerage (those with titles of nobility), gentlemen, common

people, and slaves at the bottom. One's life was determined by one's birth. The

American Revolution got rid of this entire system of aristocracy. There is even

a clause in the Constitution prohibiting the granting of titles of nobility in

America. Historian Gordon Wood states: The American Revolution was integral to

the changes occurring in American society, politics and culture .... These

changes were radical, and they were extensive .... The Revolution not only

radically changed the personal and social relationships of people, including

the position of women, but also destroyed aristocracy as it'd been understood

in the Western world for at least two millennia.

In the 15th century, it would not be surprising for Florentine

scholars, who were part of the elite, to view the uprising negatively. Leonardo

Bruni regarded the uprising as a mob out of control, whose members viciously

looted and murdered the innocent. He viewed this event as a historical

cautionary tale, which presented the horrendous consequence when rabbles

managed to seize control from the ruling class. In the 16th century, Niccolo

Machiavelli harbored a somewhat different view than Bruni. Although he echoed

Bruni's perspective, also referring to them as the mob, the rabbles,

preoccupied by fear and hatred, he was more favorable than Bruni in viewing the

event as a whole. According to Machiavelli, the revolt was a social phenomenon

between one group of people, who were determined to obtain freedom, while the

other determined to abolish it.

In Florence Guild rule then continued virtually unchallenged

until 1378. Then there was a movement in the city to check the disastrous

consequences of this tyrannical power, and to widen the Government; the leader

of the movement was a respectable citizen of the middle class, Salvestro de'

Medici. In order to obtain their desire, the supporters of the new movement

called in the aid of the lower classes, and suddenly all the discontent of the disenfranchised

class, oppressed both politically and industrially, broke into flame, and Florence

was involved in a bloody war between labor and capital. In that year the regime

was overthrown not by signore but by factions within the ruling class, which in

turn provoked the remarkable proletarian Revolt of the Ciompi. In the

wool-cloth industry, which dominated the manufacturing economy of Florence, the

lanaioli (wool entrepreneurs) worked

on the putting-out system: they employed large numbers of people who worked in

their own homes with tools supplied by the lanaioli

and received wages by the piece. Largely unskilled and semiskilled, these men

and women had no rights within the guild and in fact were subjected to harsh

controls by the guild. In the Arte della

lana (the wool-cloth guild), a “foreign” official was responsible for

administering discipline and had the right to beat and even torture or behead

workers found guilty of acts of sabotage and theft. The employees, who were

often in debt (frequently to their employers), subsisted precariously from day

to day, at the mercy of the trade cycle and the varying price of bread. With

them, among the ranks of the popolo

minuto (“little people”), were day laborers in the building trades as well

as porters, gardeners, and poor and dependent shopkeepers. In effect, the poor

rose to revolt only at the prompting of members of the ruling class. So it was

in the Revolt of the Ciompi of 1378. In June of that year Salvestro de’ Medici,

in an attempt to preserve his own power in government, stirred up the lower

orders to attack the houses of his enemies among the patriciate. That action, coming at a time when large numbers of

ex-soldiers were employed in the cloth industry, many of them as Ciompi (wool

carders), provoked an acute political consciousness among the poor. In their clamor

for change, the workers were joined by small masters resentful of their

exclusion from the wool guild, by skilled artisans, and by petty shopkeepers.

Expectation of change and discontent fed upon each other. In the third week of

July, new outbreaks of violence, probably fomented by Salvestro, brought

spectacular change: the appointment of a ruling committee (Balia) composed of a

few patricians, a predominating number of small masters, and 32 representatives

of the Ciompi. The leaders of the original movement and their aims were swept

aside; for some months Florence was in the hands of a turbid mob, which would

not be content without obtaining a full share in the management of politics as

a means to economic reform. They wanted industrial equality for all the Guilds,

and suggested a sliding scale of taxation as a means to equalize wealth. In

their six-week period of rule, the men of the Balia sought to meet the demands

of the insurgents.

The outward movement of European peoples in any substantial

numbers naturally was tied in with conquest and, to a greater or lesser degree,

with the displacement of indigenous populations. In the United States, where by

far the largest number of European emigrants went, acquisition of space for

development by white immigrants entailed activity on two fronts: competition

with rival European nations and disposition of the Indians. During a large part

of the 19th century, the United States remained alert to the danger of

encirclement by Europeans, but in addition the search for more fertile land,

pursuit of the fur trade, and desire for ports to serve commerce in the

Atlantic and Pacific oceans nourished the drive to penetrate the American

continent. The U.S. government feared the victorious European powers that

emerged from the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815) would revive monarchical

government. France had already agreed to restore the Spanish monarchy in

exchange for Cuba. As the revolutionary Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) ended,

Prussia, Austria, and Russia formed the Holy Alliance to defend monarchism. In

particular, the Holy Alliance authorized military incursions to re-establish

Bourbon rule over Spain and its colonies, which were establishing their

independence. Ever since the 17 republics of mainland Latin America emerged

from the wreck of the Spanish Empire in the early 19th century, North Americans

had viewed them with a mixture of condescension and contempt that focused on

their alien culture, racial mix, unstable politics, and moribund economies. The

Western Hemisphere seemed a natural sphere of U.S. influence, and this view had

been institutionalized in the Monroe Doctrine of 1823 warning European states

that any attempt to “extend their system” to the Americas would be viewed as

evidence of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States itself. On the

one hand, the doctrine seemed to underscore republican familiarity, as

suggested by references to “our sister republics,” “our good neighbors,” our

“southern brethren.” On the other hand, the United States later used the

doctrine to justify paternalism and intervention. This posed a quandary for the

Latin Americans, since a United States strong enough to protect them from

Europe was also strong enough to pose a threat itself. When Secretary of State

James G. Blaine hosted the first Pan-American Conference in 1889, Argentina

proposed the Calvo Doctrine asking all parties to renounce special privileges

in other states. The United States refused. The American Anti-Imperialist

League was an organization established on June 15, 1898, to battle the American

annexation of the Philippines as an insular area. The anti-imperialists opposed

expansion, believing that imperialism violated the fundamental principle that

just republican government must derive from "consent of the

governed." The League argued that such activity would necessitate the

abandonment of American ideals of self-government and non-intervention—ideals

expressed in the United States Declaration of Independence, George Washington's

Farewell Address and Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address. The Anti-Imperialist

League was ultimately defeated in the battle of public opinion by a new wave of

politicians who successfully advocated the virtues of American territorial

expansion in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War and in the first years

of the 20th century. Around the year 1900, most of those colonial possessions

in North and South America were independent but something dramatic happened in

Africa and in much of Asia. Africa had now been carved up by the colonial

powers.

The Balia approved the formation of guilds for the wool carders and

other workers to give standing to their members, established more-equitable

taxation between rich and poor, and declared a moratorium on debt. Yet, angry

at the slow pace of change, the poor remained restive. On August 27 a vast

crowd assembled and proceeded to the election of the “Eight Saints of God’s

People.” Then they marched on the Palazzo Vecchio with a petition that the

Eight Saints should have the right to veto or approve all legislation. But by

now all the temporary allies of the poor were alienated from the spirit of

revolt. The rich resisted, won over “standard-bearer of justice.” with a bribe,

called out the guild militias, and drove the protesters from the scene. The revolt

was crushed, its principal leaders banished, and the oligarchy became almost as

powerful and narrow as before. The lower classes were utterly excluded from the

Government; the share of the Minor Arts in the Government offices was fixed at

one-quarter, the Parte Guelph nominally restored. Yet the real changes wrought

by this "Ciompi" rebellion were very great. The power of the Guilds

as political associations was really gone; the Parte Guelph never recovered its

authority, and in the fifteenth century it was nothing but a name. The main

effect of the revolt was to introduce at the top of society a regime that was

narrower and more oligarchic than that which had ruled for the previous 30

years. Following the collapse of the Revolt of the Ciompi, Florence itself had

come under the rule of a narrow oligarchic government under the personal

domination of Maso degli Albizzi (1382–1417).

By the 17th century there was already a tradition and awareness

of Europe: a reality stronger than that of an area bounded by sea, mountains,

grassy plains, steppes, or deserts where Europe clearly ended and Asia

began—“that geographical expression” which in the 19th century Otto von

Bismarck was to see as counting for little against the interests of nations. In

the two centuries before the French Revolution and the triumph of nationalism

as a divisive force, Europe exhibited a greater degree of unity than appeared

on the mosaic of its political surface. With appreciation of the separate interests

that Bismarck would identify as “real” went diplomatic, legal, and religious

concerns which involved states in common action and contributed to the notion

of a single Europe. King Gustav II Adolf of Sweden saw one aspect when he

wrote: “All the wars that are afoot in Europe have become as one.” Otto von

Bismarck was a conservative German statesman who masterminded the unification

of Germany in 1871 and served as its first chancellor until 1890, in which

capacity he dominated European affairs for two decades. He had previously been

Minister President of Prussia (1862–1890) and Chancellor of the North German

Confederation (1867–1871). He provoked three short, decisive wars, against

Denmark, Austria, and France. Following the victory against Austria, he

abolished the supranational German Confederation and instead formed the North

German Confederation as the first German national state, aligning the smaller

North German states behind Prussia, and excluding Austria. Receiving the

support of the independent South German states in the Confederation's defeat of

France, he formed the German Empire – which also excluded Austria – and united

Germany. With Prussian dominance accomplished by 1871, Bismarck skillfully used

balance of power diplomacy to maintain Germany's position in a peaceful Europe.

To historian Eric Hobsbawm, Bismarck "remained undisputed world champion

at the game of multilateral diplomatic chess for almost twenty years after

1871, [and] devoted himself exclusively, and successfully, to maintaining peace

between the powers". However, his annexation of Alsace- Lorraine

(Elsaß-Lothringen) gave new fuel to French nationalism and Germanophobia.

Bismarck's diplomacy of Realpolitik and powerful rule at home gained him the

nickname the "Iron Chancellor". German unification and its rapid

economic growth was the foundation to his foreign policy. He disliked

colonialism but reluctantly built an overseas empire when it was demanded by

both elite and mass opinion. Juggling a very complex interlocking series of

conferences, negotiations and alliances, he used his diplomatic skills to

maintain Germany's position.

Once Albizzi oligarchic regime set in Florence, The oligarchy

had therefore to find means both to keep the executive entirely within its own

control and to perform its functions for it; and so weak was it that the

oligarchs, as long as they were united amongst themselves, found little

difficulty in managing it. First it was necessary to make sure that no person

could obtain any office of importance who was not a member of the ruling party,

or could not be thoroughly trusted by it. For many years the oligarchy ruled

Florence successfully. During the latter years of the fourteenth century the

strength of the Republic was strained to the uttermost in her conflict with

Gian Galeazzo Visconti, the powerful and unscrupulous Duke of Milan. The strong

executive needed to resist him successfully was found in the oligarchy. After

his death the Republic accomplished one of the most brilliant feats in her history,

the conquest of Pisa; and during the earlier years of the fifteenth century she

was involved in another life and death struggle with Ladislas of Naples. At the

death of Ladislas in 1414, the oligarchy was at the summit of its power.

"One may rightly say," declares Guicciardini, the most impartial of

all authorities, "that it was the wisest, the most glorious, the most happy

government that our city has ever had." All foreign enemies were crushed;

the territory of the Republic was increased by the addition of Pisa and Cortona;

while the possession of Pisa gave Florence a new access to the sea, and filled

her with ambitions to succeed to the naval power of the captured city. The

oligarchs had so far been held together by the pressure of foreign wars, and

the fear of a repetition of the "Ciompi" rebellion, in which so many of

their relatives perished. They were becoming an hereditary clique, to which

certain families alone were admitted, and a tendency towards the descent of a position

in the Government from father to son was beginning to gain ground. Thus, on the

deaths of Maso degli Albizzi and of Matteo Castellani their eldest sons,

Rinaldo and Francesco, the latter only a child, were knighted with great

ceremony by the Commune, as if to take their fathers' places. " The city

of Florence," wrote a contemporary, "was at this time in the most

happy condition, full of men gifted in every direction, each one trying to

surpass the other in merit." Supreme amongst these were half a dozen men

whose wealth, wisdom, and political experience enabled them to lead the others.

These were Gino Capponi, the “Conqueror of Pisa,” Lorenzo Ridolfi, Agnolo

Pandolfini, Palla Strozzi, Matteo Castellani, Niccolo Uzzano all men who took

part in the Pratiche, conducted foreign embassies, sat in the Dieci, and

frequently held other offices. But the chief of all was Maso degli Albizzi, whose

ability and energy had enabled him to gain so commanding a position that it

almost seemed as if before long the Rule of the Few might be converted into the

Rule, of One.

On the 18th of January

1871, at the Palace of the side, the German leaders declared the creation of

the German Empire, with Wilhelm I as emperor. A unified Germany quickly became

a great power. Bismarck negotiated an alliance with the Austro-Hungarian

Empire, and managed to secure some African colonies by calling the Berlin

Conference with the other European powers. It experienced a population boom

alongside rapid industrialization and urbanization, and also became a global

center of science. Advances in ship construction (steamships using steel hulls,

twin screws, and compound engines) made feasible the inexpensive movement of

bulk raw materials and food over long ocean distances. Under the pressures and

opportunities of the later decades of the 19th century, more and more of the

world was drawn upon as primary producers for the industrialized nations.

Self-contained economic regions dissolved into a world economy. Germany was a latecomer in the Empire Race, which was already

well underway when the country was unified in 1871. Germany, like other

European powers, wanted the honor and prestige of having a colonial empire.

German foreign policy in that period was intensely nationalistic; it changed

from Realpolitik to the more

aggressive Weltpolitik in an effort

to expand the German Empire. When the German Empire came into existence in

1871, none of its constituent states had any overseas colonies. Only after the

Berlin Conference in 1884 did Germany begin to acquire new overseas

possessions, but it had a much longer relationship with colonialism dating back

to the 1520s. Before the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, various German

states established chartered companies to set up trading posts; in some

instances they also sought direct territorial and administrative control over

these. After 1806, attempts at securing possession of territories overseas were

abandoned; instead, private trading companies took the lead in the Pacific

while joint-stock companies and colonial associations initiated projects

elsewhere, although many never progressed beyond the planning stage. It was in

Africa that Germany made its first major bid for membership in the club of

colonial powers: between May 1884 and February 1885, Germany announced its

claims to territory in South West Africa (now Namibia), Togoland, Cameroon, and

part of the East African coast opposite Zanzibar. Two smaller nations, Belgium

and Italy, also entered the ranks, and even Portugal and Spain once again

became active in bidding for African territory. The increasing number of

participants in itself sped up the race for conquest. And with the heightened

rivalry came more intense concern for preclusive occupation, increased

attention to military arguments for additional buffer zones, and, in a period

when free trade was giving way to protective tariffs and discriminatory

practices in colonies as well as at home, a growing urgency for protected

overseas markets. Not only the wish but also the means were at hand for this

carving up of the African pie. Repeating rifles, machine guns, and other

advances in weaponry gave the small armies of the conquering nations the

effective power to defeat the much larger armies of the peoples of Africa. Although there are

sharp differences of opinion over the reasons for, and the significance of, the

“new imperialism,” there is little dispute that at least two developments in

the late 19th and in the beginning of the 20th century signify a new departure;

first that notable speedup in colonial acquisitions and an increase in the number

of colonial powers. The annexations during this new phase of imperial growth

differed significantly from the expansionism earlier in the 19th century. While

the latter was substantial in magnitude, it was primarily devoted to the

consolidation of claimed territory (by penetration of continental interiors and

more effective rule over indigenous populations) and only secondarily to new

acquisitions. The new imperialism was distinguished particularly by the

emergence of additional nations seeking slices of the colonial pie: Germany,

the United States, Belgium, Italy, and, for the first time, an Asian power,

Japan. Indeed, this very multiplication of colonial powers, occurring in a

relatively short period, accelerated the tempo of colonial growth. Unoccupied

space that could potentially be colonized was limited. Therefore, the more

nations there were seeking additional colonies at about the same time, the

greater was the premium on speed. Thus, the rivalry among the colonizing

nations reached new heights, which in turn strengthened the motivation for preclusive

occupation of territory and for attempts to control territory useful for the

military defense of existing empires against rivals.

Yet when the pressure, of war and the fear of a new "Ciompi"

were removed,' the oligarchy began to suffer from that weakness which sooner or

later causes the ruin of all oligarchies-internal dissension. The least important

of its members were jealous of 'the greater, and all were jealous of Maso degli

Albizzi. The party began to split up in small cliques, mainly on family lines,

each struggling for the supremacy. Maso Albizzi’s strong hand was removed in

1417, but even before his death there were signs that his supreme authority was

not unquestioned. Gino Capponi had headed a

party which objected to the last peace signed with Ladislas in 1414; Maso had the

greatest difficulty in obtaining its confirmation by the Councils; Gino was

even accused of a plot against Maso's life. Rinaldo degli Albizzi, Maso's son,

a young man of great talents, who had already served an apprenticeship in most

of the Government offices and in numerous foreign embassies, was probably ill contented

with Uzzano's supremacy, and there were others of the younger generation who

showed signs of resenting the authority of the older and wiser heads. Yet for

years it is impossible to find any organized opposition within the ranks of the

ruling party, only there was general discontent, and constant complaints of the

want of union in the Government, and of the way in which public affairs were

conducted by private cabals. Even the Pratiche were becoming shams, when Uzzano

and his personal friends had decided before the Pratica met what policy they meant to adopt; and, after the uninitiated

had been allowed to amuse themselves by airing their several opinions, Uzzano,

who had apparently been asleep throughout the discussion, woke, stood up and

explained his views, to which his followers immediately expressed their

adhesion. The disunion of the Government was the cause of the gradual, but

steady, revival of those parties which had been crushed by the oligarchy after

the suppression of the “Ciompi” rebellion. Chief amongst them were the members

of the Minor Arts, who were excluded from all but a small share in the

government; and also a great number of those members of the Major Arts who, though

theoretically capable of office, were unable to pass the Scrutinies. Others again

had passed the Scrutinies and could hold office, but yet were without influence

in the Government, because they did not chance to" belong to one of the

families of which the ruling party was composed. The last quarter of a century

had seen a great increase in the wealth of these excluded classes; they were

already as rich as, or richer than, the members of the oligarchy, and naturally

wished their political position to correspond with the" social standing given

them by their wealth. They were by degrees reinforced by all the elements of

discontent within the city. There were the Grandi, heavily taxed, and almost

unrepresented in the Government; and there were the lower classes, who also

thought themselves unfairly taxed, and whose interests the Government never

seemed inclined to take into the smallest account in deciding any question of

policy. Maso degli Albizzi had had the wisdom to conciliate this class by a

popular economic policy, and personally he was much liked, but his successors

did not continue in his steps. Yet it was long before these various elements

could coalesce. At present there was only a good deal of discontent, slowly and

steadily spreading; but there was nothing like a united party, nor there any

common leader.

Wilhelm I died in 1888. He was replaced by Friedrich III, who

died 99 days later. And he was followed by Wilhelm II. Wilhelm wanted to assert

his own independence, and so encouraged Bismarck to resign in 1890. Imperial

German had plans for the invasion of the United States which were ordered by

Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm II from 1897 to 1903. He intended not to conquer the

US but only to reduce the country's influence. His planned invasion was

supposed to force the US to bargain from a weak position and to sever its

growing economic and political connections in the Pacific Ocean, the Caribbean

and South America so that German influence could increase there. Junior officers

made various plans, but none were seriously considered and the project was

dropped in 1906. Unlike his predecessors, Wilhelm II was very hot-headed and

prone to immediate reaction. He was also determined to increase the prestige of

Germany. He did this by undertaking a major naval build-up in the early 20th

century. This upset Britain. Britain had previously kept itself out of European

affairs, but the large German navy posed a threat to its naval hegemony and

could even threaten the British mainland. So in 1914, the Archduke Franz

Ferdinand was assassinated by a Serbian nationalist, and the established series

of alliances and counter-alliances plunged Europe into World War One. Some historians prefer to divide 19th-century history into

relatively small chunks. Thus, 1789–1815 is defined by the French Revolution and

Napoleon; 1815–48 forms a period of reaction and adjustment; 1848–71 is

dominated by a new round of revolution and the unifications of the German and

Italian nations; and 1871– 1914, an age of imperialism, is shaped by new kinds

of political debate and the pressures that culminated in war. The new imperialism

was characterized by a burst of activity in carving up as yet independent

areas: taking over almost all Africa, a good part of Asia, and many Pacific

islands. This new vigor in the pursuit of colonies is reflected in the fact

that the rate of new territorial acquisitions of the new imperialism was almost

three times that of the earlier period. By the beginning of that World War one,

the new territory claimed was for the most part fully conquered, and the main

military resistance of the indigenous populations had been suppressed. Hence,

in 1914, as a consequence of this new expansion and conquest on top of that of

preceding centuries, the colonial powers, their colonies, and their former

colonies extended over approximately 85 percent of the Earth’s surface.

Economic and political control by leading powers reached almost the entire

globe, for, in addition to colonial rule, other means of domination were

exercised in the form of spheres of influence, special commercial treaties, and

the subordination that lenders often impose on debtor nations.

Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species in 1859, and

within a decade popularizers had applied—or misapplied—his theories of natural

selection and survival of the fittest to contemporary politics and economics.

This pseudoscientific social Darwinism appealed to educated Europeans already

demoralized by a century of higher criticism of religious scripture and

conscious of the competitiveness of their own daily lives in that age of

freewheeling industrial capitalism. By the 1870s books appeared explaining the

outcome of the Franco-German War, for instance, with reference to the

“vitality” of the Germanic peoples by comparison to the “exhausted” Latins.

Pan-Slavic literature extolled the youthful vigour of that race, of whom Russia

was seen as the natural leader. A belief in the natural affinity and

superiority of Nordic peoples sustained Joseph Chamberlain’s conviction that an

Anglo-American–German alliance should govern the world in the 20th century.

Vulgar anthropology explained the relative merits of human races on the basis

of physiognomy and brain size, a “scientific” approach to world politics occasioned

by the increasing contact of Europeans with Asians and Africans. Racialist

rhetoric became common currency, as when the kaiser referred to Asia’s growing

population as “the yellow peril” and spoke of the next war as a “death struggle

between the Teutons and Slavs.” Poets and philosophers idealized combat as the

process by which nature weeds out the weak and improves the human race.